Alvin

Fig. 1. Alvin's first days. Photo courtesy of WHOI.

The research minisub Alvin was born at a 1956 Washington, D.C., symposium when Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientist Allyn Vine and other researchers drafted a proposal to develop such an undersea vehicle. Its first version was fabricated out of steel in 1962, and the Deep Submergence Group (DSG) was begun at Woods Hole to maintain and pilot it. Its name was both a contraction of Vine's first and last name and a reference to the well-known cartoon singing chipmunk. In 1965, Alvin's first tender - named LULU for Vine's mother - was built around two Navy surplus pontoons. The following year Alvin was sent to the Mediterranean, where the sub located an undetonated H-bomb that had been lost after a military mid-air collision.

In the 1970s Alvin acquired a new pressure hull and frame made of titanium. Over the years, it has been repeatedly refitted until no trace of the original vessel remains. And in the 1980s LULU was replaced as mother ship by the larger Atlantis II, predecessor of its current at-sea home. In July, 1986, the sub made a series of highly-publicized dives to the remains of the H.M S. Titanic, which a previous generation of the Argo towed camera vehicle had first spotted, with Crook on the watch team. Before and since, it has helped rewrite textbooks on undersea geology, oceanography and biology while visiting scores of scientific study sites, including our undersea mountain.

Today Alvin dives to the Atlantis Massif.

Launching Alvin

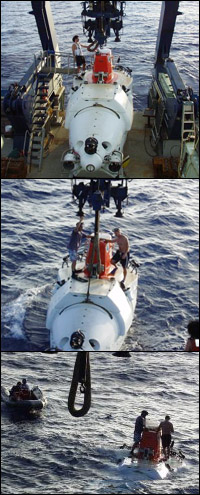

Alvin launches and recoveries are a kind of ballet involving the R/V Atlantis, the fiberglass-bottomed black-and-red inflatable powerboat called the Avon, and flipper-wearing "swimmers" who courageously ride the sub down from and up to the ship's fantail as well as dive into the open ocean to see to Alvin's needs.

This nautical choreography "has evolved through the years, ever since we started doing it on Atlantis II," said Gary Chiljean, the current R/V Atlantis's Master, or captain. "Whenever we saw a need for improvements, we did it." The maneuvers demand deft coordination between the Alvin's DSG and Atlantis' crew. Some crew members serve as the fast-moving Avon's pilots - called "coxswains" - and some train to be swimmers just like the Alvin team.

The seven-member Alvin group's workday begins with 6 a.m. pre-launch checks. For Atlantis's crew of 22, work never stops. Someone in the engineering department may be busy desalinating seawater so scientists can take a pre-dive shower. A little later, someone in the galley is up making their early breakfasts.

By 8 a.m. the sub has been rolled out of its hanger and back to Atlantis's fantail along a special curved railroad track. Shortly afterwards diving scientists are escorted up to the top of the access ladder, place their shoes in a blue bag, pivot their legs awkwardly over the stubby red conning tower (or "sail"), and begin wriggling down through the small hatch in their stocking feet. After that hatch is sealed, the "A-Frame", a tall A-shaped hoist on Atlantis's stern, pulls the Alvin up from its cradle on a thick and beautifully-braided rope. Next the A-Frame itself pivots backwards so that the sub is dangling over the water, with two swimmers clinging to its tiny deck. As soon as Alvin is lowered down into the rolling ocean, the wave-tossed swimmers remove the big rope before diving into the water and breast stroking to the waiting Avon.

Fig. 2. Launch image sequence. (a) Alvin in A-Frame. (b) Lowering Alvin into the water. (c) Alvin and divers in the water, free of the ropes.

Soon Alvin disappears from view after the pilot increases the craft's weight by letting seawater into a ballast tank. But a DSG team member, usually a pilot, keeps tabs via sonar and underwater telephone from the "top lab" up in Atlantis' operations center, or "bridge." Top lab watch standers track the sub's entire trip, as best as communications and available spotty navigation allows. To the accompaniment of watery sounding sonar "pings," they type updated positions into a computer that charts Alvin's progress on two video monitors. On-screen, the sub's course is shown in blue and the ship's position in red.

Sometimes the t op lab communicator also serves as switchboard operator for scratchy satellite "phone patch" telephone calls between diving science team members and their loved ones back home. Such calls are expensive and a bit awkward, with the top lab having to toggle between home and sub and the callers having to end each transmission with "over." But even grizzled veteran pilots have been known to yield to the temptation.

"I called my dad on his 63rd birthday from the bottom," recalled Alvin pilot Williams on Saturday, Nov. 25, after patching Scripps graduate student Scott Nooner in with his wife from a depth of 2,700 meters. "My dad was out working in the yard. Mom said it was all he talked about for two weeks."

Today's pages:

Alvin: History and Launch | Alvin Recovery | Under the Sea | Dredging

|